The heaviness of this protest cannot be overstated.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1971_Vietnam_veteran_medal_throwing_protest

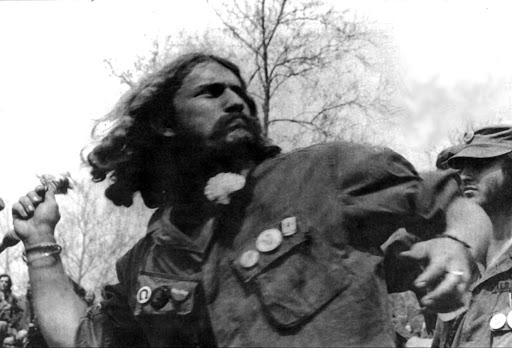

The early days were filled with marches of hundreds of veterans, often led by men in wheelchairs and on crutches, wearing "a wild assortment of campaign ribbons, purple hearts, camouflage half uniforms, and jungle camouflage hats"; guerrilla theater on Capital Hill, where vets staged mock search-and-destroy missions showing how U.S. troops were ordered to kill everything that moved and demonstrating that the Mỹ Lai massacre was not an aberration; and lobbying of members of congress.[6]

The growing anger of the veterans helped them decide what to do on the last day of the demonstrations. As one vet explained, "I remember there was a big debate about whether we should throw the medals away at the Capitol Building or put them in a body bag."[4]: p.111 Some of the less radical vets felt it would be disrespectful to throw the medals away, but, as the debate continued, a fence was erected in front of the Capitol to keep the vets away. That was it, one of the vets shouted "Let's throw the medals over the goddammed fence." Another said, "We're making a statement that they can't ignore."[8]: p.249 The veterans were making a significant decision. As history professor Andrew E. Hunt put it, "In the military culture, citations, ribbons, and decorations assumed a significance that most civilians did not understand." Hunt quoted a vet explaining what his medals meant to him, "That was my thanks for Vietnam. That was my recognition. That was all the fuck I had for my sacrifices." Over time, however, the vet understood the medals were "tokens for something I wasn't proud of anymore."[4]: p.113 Another vet knew what they needed to do, "We were giving the finger to Congress."[4]: p.115

The first veteran to step forward was Jack Smith, a 27 year old ex-Marine sergeant from Connecticut. He said he was casting his medals "away as symbols of shame, dishonor, and inhumanity."[4]: p.113 One by one, the veterans stepped up in front of the Capitol and hurled their anger over the fence. Many announced their name and military unit, and some threw medals for other vets who couldn't be present, including one vet who tossed "nine Purple Hearts, a Distinguished Service Cross, a Bronze Star, a Silver Star 'and a lot of other shit...for my brothers.'"[4]: pp.113–4 One vet threw the artificial leg he had been issued by the military.[4]: p.114 Another tossed his Bronze Star saying, "I wish I could make them eat it!"[5]: p.72 Some were so overcome upon reaching the front of the line they couldn't speak or could only get out a few words like, "These ain't shit." Another yelled "Here are my merit badges for murder." A former Marine told the New York Times why he was throwing his medals away: he said he had been trained not to "trust the kids, don't trust the old women, they'll kill you." But, he went on, "It's the people's struggle against the aggressor, [and] we're the aggressor."[9] One veteran, seemingly speaking for many of the others, pointed to the Capitol building and said, "We don't want to fight anymore, but if we have to fight again, it'll be to take these steps."[4]: p.115

After the last veteran had thrown his medals, "fourteen Navy and Distinguished Service Crosses, one hundred Silver Stars, and more than a thousand Purple Hearts lay on the ground."[4]: p.115

Edit: I don't know if this applied to this protest, but one account described one of the VVAW protests and said that it was absolutely silent. No chanting, no slogans, no yelling. Just men in uniform with dark, angry expressions on their faces, quietly walking or in wheelchairs, moving in organized rows with people giving hand signals for where the column was going to go next or when it would pause in place. He said it was absolutely impossible to watch and not get quiet and watch seriously until it had passed by.